If 72 is the New 30, Is 150 the New 70?

February 28, 2013

Demographers comparing the lifespans of hunter-gatherers to lifespans in the modern era recently reported that the average 30-year-old hunter-gatherer had about the same odds of dying as a Swedish or Japanese man faces at age 72.

Media promptly declared that “72 is the new 30,” and posted pictures of famous septuagenarians such as Chuck Norris, Al Pacino, and Raquel Welch – all extremely healthy and active. The reports hinted at the enticing prospect of living much longer than we currently do.

This prompts the following question: If 72 is the new 30, is 150 the new 70? While this might seem absurd at first blush, there is no doubt that lifespans have been expanding inexorably since the mid-1800s, as the demographers concluded. And with advances in medical technology and gene therapy, the trend will surely continue. The question is not whether we will live longer in the future, but by how much.

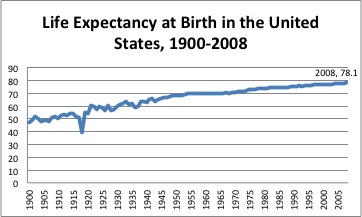

Take a look at how far we have come in the United States. In 1900, the average lifespan at birth was just over 47. In 2000, the average lifespan had increased by over 60% to 77 years. As of 2008, it had increased to 78.1, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (p 46). If average lifespans at birth increase by another 60% this century, we will be living to 124 years of age – and that’s just an average. Some will be living much longer.

Life Expectancy at Birth, 1900-2008

Barring major medical or genetic breakthroughs, an average lifespan of 150 years in our lifetimes is far-fetched. But split the difference between the current average lifespan and 150, and we get 111. While truly old, this is not out of the realm of possibility as humans are indeed living to this age or longer. In fact, the Social Security Administration calculates the probability of dying up to the age of 119 (there is a 91.3855% chance of dying at age 119, according to the SSA.) Look at the story of the Marathon Sikh, who retired from running at the sprightly young age of 101.

And who wouldn’t want to live a long and fruitful life into their 100s? This is definitely a good-news story.

The challenge is paying for it. Take the FERS pension, for example. Let’s say a worker retires at the age of 62 after 37 years of work. He’ll get 40.7% of his base pay as a pension (retiring at 62, FERS employees receive 1.1% multiplied by years worked). For ease of calculation, let’s say that is $2,500 a month, or $30,000 a year, from a high-three average salary of $75,000. That’s reasonable after almost four decades of work, right?

Now let’s project that out over an expanded lifespan through age 111. With a 3% cost-of-living adjustment each year, if this individual lives to 111 his $2,500 monthly pension would have grown to over $10,600 a month, or $127,686 a year. His pension will have doubled twice over. His pension, which was originally 40% of his salary, would now be 160% of his high-three average salary. He would have lived 49 years in retirement – 12 years more than he spent working.

The same basic calculation applies to Social Security. Let’s say this individual begins to draw a reduced Social Security benefit at 62 of about $1,000. (Social Security Administration calculators can be accessed on the ssa.gov site.) Again for ease of calculation, let’s say his benefit rose by 3% each year. His monthly benefit at age 111 would have grown from $1,000 a month or $12,000 a year at age 62 to over $4,200 a month – or over $50,000 a year.

I know, critics will say these yearly 3% increases are just adjustments for yearly inflation, etc etc., and that there is no “real” increase in payouts. But there is no doubt, these are whopping numbers that grow inexorably over decades, to be borne entirely by future taxpayers.

When Social Security first began in the mid-1930s, the average lifespan (about 62) was several years less than the age to begin collecting benefits. Government workers were similarly eligible to collect a pension only at a decade above the average lifespan in the 1920s and 1930s. Now, lifespans have increased dramatically, while retirement ages have stayed the same or declined. And Social Security taxes have at the same time increased from 1% in the 1930s to 12.4% today, yet this is still not enough to support the growing number of Social Security recipients. Given this trend, could it be that current and future tax increases will again not be enough to support the increasing number of Social Security and pension recipients?

Indeed, there is a reason Social Security’s main benefit is called “Old Age and Survivors Insurance” and not called “retirement insurance” – it was never meant as a retirement program. According to the Social Security website, President Roosevelt himself pointed this out in 1938 when he spoke about the Social Security Act:

“The [Social Security] Act does not offer anyone, either individually or collectively, an easy life–nor was it ever intended so to do. None of the sums of money paid out to individuals in assistance or in insurance will spell anything approaching abundance. But they will furnish that minimum necessity to keep a foothold; and that is the kind of protection Americans want.”

The opposite is true for the Thrift Savings Plan, which is an employer-worker partnership in building wealth. While there is significant debate in Congress and from the White House about how to control Social Security, Medicare, and pension costs as part of reducing the recurring $1 trillion deficits, there is no debate about maintaining the TSP benefit.

Ultimately, we are living longer. Should we routinely live into our 100s, this will bankrupt the system altogether – as it stands, the system is under tremendous pressure even with current lifespans, which continue to increase year after year.

There are multiple reasons for this:

-

Recipients are drawing benefits years longer than they worked, under a pay-as-you-go system that places all of the burden on the shrinking number of current workers.

-

Cost-of-living increases mean these transfers of payments from current taxpayers to retirees increase each year.

-

As more people live longer in retirement, older workers – who are currently paying taxes – are increasingly leaving the workforce, causing the ratio of Social Security and government pension recipients to taxpayers to increase. Relatively fewer taxpayers are having to pay for an increasing number of retirees.

Simply put, we cannot continue to collect benefits at roughly the same age as 60 years ago but live 50% longer than we did then. Is this fair to taxpayers in 2050, in other words, those who are just being born today?

This is not to say that workers could not leave the workforce early — through diligent planning and investing, a worker could conceivably leave the workforce and live an independent life on savings generated in the TSP and other investment vehicles, with perhaps a delayed pension that is paid out later in life. But this is based on individual initiative and hard work, and not based on an increasingly unfair benefits system.

But these are the megatrends that are putting inexorable pressure on the current “benefit” structure, and these are the reasons why the TSP and other wealth-building mechanisms like Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) and Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) will become an ever more important part of our benefits packages. We must be prepared for changes, for our kids’ and grand kids’ sakes if not for our own.

Related topics: longevity hsa